As I leave my SAT preparation course, I find myself shaking my head, angry at the world. Specifically speaking, I’m angry at the state of education and the values we have placed on specific expressions of intelligence.

That day in class, I learned that the girl who sits across from me, whose pattern of receiving perfect scores on all of her practice tests was, as I had conjured, a result of high intelligence, had been attending the class for four years.

Yes, four years.

Now, this does not necessarily mean that she lacks intelligence. I know that she attends Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology, but otherwise, I do not know her work ethic, grades, demeanor or other factors that might deem her intelligent.

I was not angry at her. What I was frustrated with were my own immediate conclusions. I had assumed that the perfect scores she procured were a result of her high capacity for logical reasoning, assuming that she had been in the class for the same amount of time as I had.

I realized, furthermore, that my conclusions are based on a society that increasingly values standardized testing as a measure of one’s intelligence over other factors, such as artistic abilities, the ability to speak well or one’s skill of persuasion.

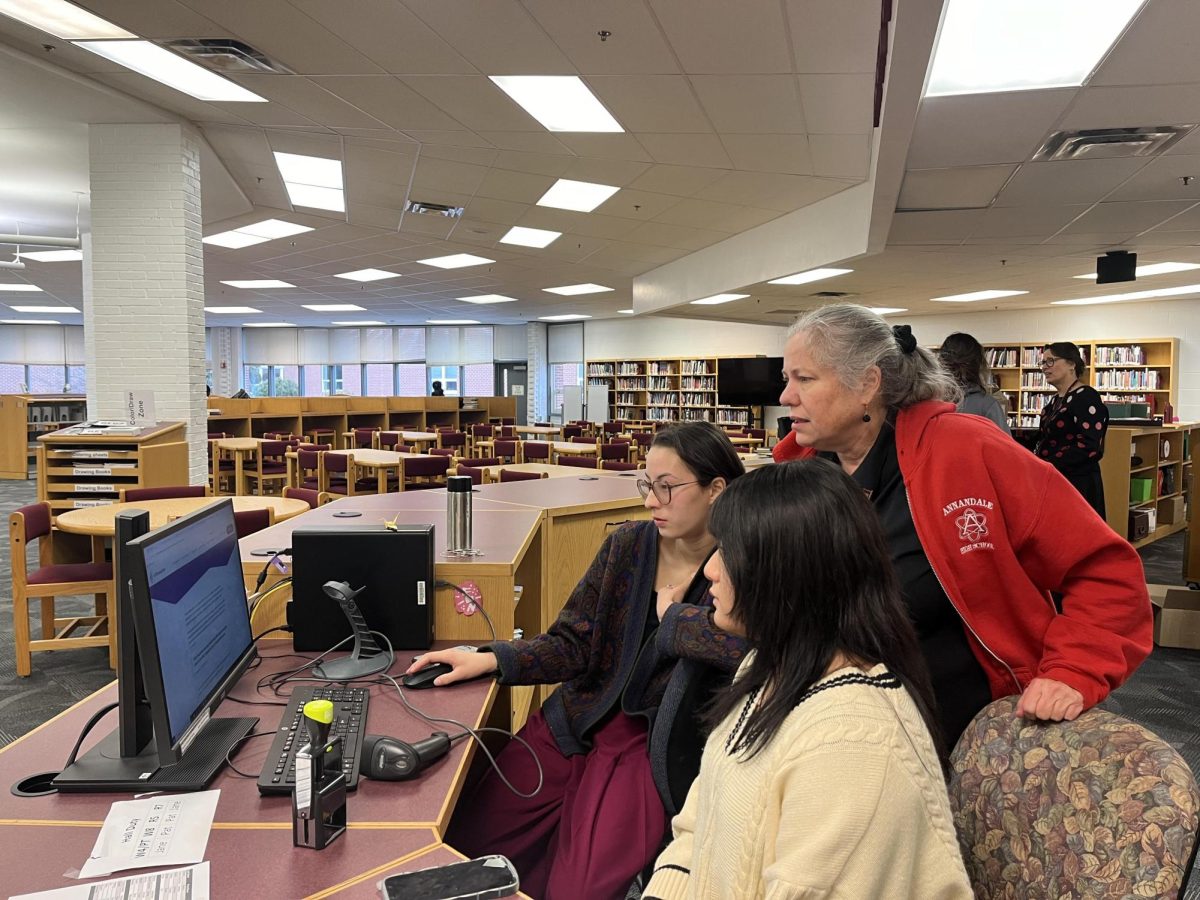

As I wrote on May 12 for The A-Blast last year, the realm of education has become startlingly reliant on standardized testing. This priority of standardized testing has now become ingrained into my own culture as a student, as illustrated by my assumptions made in the previous story.

This “double take” regarding my assumptions brought me to reflect on one looming, seemingly unanswerable question: what is intelligence?

I might assume that in today’s day and age, intelligence is contingent upon one’s test scores. Our teachers and parents have imparted to us that “grades are everything.” If this is the case, then what did society perceive as intelligence before the introduction of grades to the western model of education?

Yes, believe it or not, grades did not always exist, nor did report cards. In fact, they have only been popularly used in the United States for 160 years. Beforehand, prior to the 1850s, intelligence was perceived through many forms. The ability to write, to persuade and to think (not in the superficial sense that we associate with “think” today) were markers of intelligence.

So after understanding this brief excursion into history, what should we call intelligence? In the end, do grades matter? Are SAT scores really that important? Unfortunately, many might answer “yes.” I myself, while I write this article on a computer with a background image of Nassau Hall, the main building of Princeton University’s campus, might have come to a similar conclusion.

So, how can this change? Quite honestly, I’m not sure it can. However, that does not mean that we can’t try to revitalize this pursuit of academic excellence that we have lost, or otherwise sanctioned to be left to an older generation, while remaining a part of this culture we cannot change.

The International Baccalaureate (IB) program has already started that process, and teachers remind students that sometimes the best “prize” is not an “A,” but the knowledge gleaned from the process. However, this is not enough.

Colleges and universities need to set the example. How can one expect elementary and secondary education to change if institutions of higher learning still value SAT scores and grades as the foremost indicators of potential academic success in the admissions process?

Instead, those universities whose mission it is to prepare their young students to lead the free world must place a value similar to what was done over a century ago; on writing and on the ability to speak, to persuade and to conjure insightful thinking over a subject of choice. Thus, they should focus less so on tests, SAT scores and other means to measure truly superficial, unimportant expressions of intelligence.

Otherwise, selective high schools and universities might continue to admit students who cannot make truly insightful and meaningful assertions or arguments, who might have had a private college tutor or whose parent wrote their “personal essays” and prepared them for answers to expected interview questions. Somehow, universities need to make this change. Otherwise, we might continue to remain hostage to a system that is truly “dumbing us down.” What is an even deeper problem, and the reasoning behind this whole change in culture, is increasing pressure on high school students to determine their interests early in their school years.

Michelle Obama contributed to this culture in her recent visit to AHS, encouraging us to find our passion as soon as we can. I have to disagree with this notion. Both of my parents attended universities and pursued careers that did not pertain to their degrees whatsoever. In reality, even college students do not have the experience to determine their “passion.”

In fact, according to a recent study published in Nature magazine, such an attempt might prove futile. In this study, researchers noted that in the span of four to eight years, the IQs (Intelligence Quotients) of teenagers fell or rose by 20 points. Pertaining to my argument, such a test should not be used as an exclusive measure of intelligence. However, it certainly illustrates the uselessness in attempting to classify high school students, and even college students, into a particular “passion.”

Clearly, there is no true “answer” to this question of the nature of intelligence. However, it is clear that we should take a step back when assuming someone is “smart.” Do we assume it is because they know how to work “the system,” because they have experience or because in our society, we are impressed by one’s breadth of knowledge? Maybe it is both, but I would like to think otherwise.

Written by Noah Fitzgerel, Editorials Editor